The pre-war status of Libya's air-defense network / Sean O'Connor

Last Updated: Sunday, 6:17 a.m.

U.S. and British warships launched a barrage of cruise missiles Saturday against Libyan air defenses. It is designed to suppress the threatening systems, and the communications nodes tying them together, before an international no-fly zone is imposed over Libya to protect civilians from attack by forces loyal to Muammar Gaddafi as he clings to power.

“Today I authorized armed forces of the United States to begin a limited military action in Libya in support of an international effort to protect the Libyan civilians,” President Obama said from Brazil. “As I said yesterday, we will not, I repeat, we will not deploy any U.S. troops on the ground.”

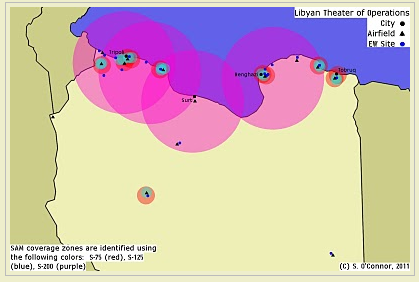

A senior Pentagon official offered limited details of what the Pentagon is calling Operation Odyssey Dawn. “Earlier this afternoon over 110 Tomahawk cruise missiles fired from both U.S. and British ships and submarines struck more than 20 integrated air defense systems and other air defense facilities ashore,” Vice Admiral William Gortney, director of the joint staff, told reporters.

The strikes hit targets largely along Libya’s Mediterranean coast. Additional attacks are likely before allied aircraft – largely European, with a smattering of Arab – begin flying the no-fly zone. The opening wave hit targets concentrated around Tripoli, the capital and where Gaddafi resides, as well as Misurata and Benghazi, a pair of rebel strongholds. For his part, Gaddafi has vowed retaliation, saying early Sunday that he would open arms depots to the people in order to defend Libya. Gaddafi said that the U.N. charter provides the nation the right to defend itself in a “war zone,” and maintained that Libyans are ready to die for him. And in an address on Libyan state TV, he said Western forces had no right to attack Libya, which had done nothing to them. Readying for a “long war,” Gaddafi said “We will fight inch by inch.”

Washington is looking to hand the operation of the no-fly zone over to its international partners, Pentagon officials said, and only played a major role in the opening salvo because its radar-killing – and electronic jamming – capabilities are unparalleled. “We anticipate the eventual transition of leadership to a coalition commander in the coming days,” Gortney said. “Our mission now is to shape the battle space in such a way that our partners can take the lead in execution.” Gen. Norton Schwartz, the Air Force chief of staff, told Congress last week that setting up the no-fly zone could take “upwards of a week” of attacks on Libya’s air-defense networks.

The initial attacks came in the wake of a 22-nation summit in Paris, led by France, Britain and the U.S. All “agreed to put in place all the means necessary, in particular military” to make Gaddafi halt attacks on civilians, French President Nicolas Sarkozy said. Gaddafi ignored the UN resolution after Thursday’s passage, and his forces continued to attack rebel positions in Benghazi and other rebel redoubts into the weekend. The first sorties are to be flown by French, British and Canadian planes, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte told the BBC, to be joined eventually by other NATO nations. U.S. military assets are largely providing intelligence and logistical support.

Many nations are committing aircraft to help attack Libyan targets in the sky and on the ground: Canada is sending six F-18s, Spain will let two of its bases be used, Britain is deploying Tornado and Typhoon warplanes, as well as aerial tankers and refueling tankers; Qatar will contribute Mirage fighters to the effort; Belgium is sending six F-16s; Italy is letting seven of its bases be used by allied aircraft against Libya; Denmark is contributing six F-16s; the Netherlands have basically said they are “going Dutch” and will contribute whatever is needed. Even Germany – which didn’t approve of the no-fly zone – may send aircrews to Afghanistan to free up U.S. crews for Libyan missions.

The U.S. military has more than a half-dozen warships involved, with hundreds of cruise missiles and airplanes ready to be deployed. It marks the third war the U.S. is now waging – or helping to wage – in a Muslim land. But there’s a big difference this time. You could discern it in Obama’s comments Friday as he warned Muammar Gaddafi to back off:

We will provide the unique capabilities that we can bring to bear to stop the violence against civilians, including enabling our European allies and Arab partners to effectively enforce a no-fly zone.

In other words, the U.S. is just tagging along – it’s other nations that are going to do the heavy lifting: “enabling our European allies and Arab partners to effectively enforce a no-fly zone.”

Like all choices when it comes to waging war, this option is fraught with opportunity and peril. It lets the U.S. participate, but in a minor key. It’s about time, many Americans will say. Why should the U.S. always be the lone cop walking the global beat? We can save money, anxiety, and lives by letting others shoulder more of the burden.

But there’s the downside, as well. By assuming a subordinate position, Washington is trying to have its cake (save the Libyans!), and eat it, too (at minimal risk to us):

— It diminishes the U.S. role as the world’s lone superpower (so does Obama’s March 3 demand that Gaddafi leave office without him doing so, at least so far). Many will view this as a good thing, as the world becomes more multi-polar, but it is a real cost.

— With Britain and France in the lead, the U.S. will have less control over what happens.

— The operation is taking place under UN Resolution No. 1973, which is interesting: 1973 was the year Congress passed the War Powers Resolution, demanding that a President consult with Congress before deploying forces for any extended military operation. In this case, the Obama Administration consulted far more extensively with its allies in foreign capitals than it did with Congress. That’s one key reason why the U.S. will hang back, militarily: Obama could end up in real trouble, politically – perhaps mortally — if any U.S. military personnel gets killed or captured in the Libyan operation.

This diplomatic dilletantism could cause problems for the President. An early volley came from Christopher Caldwell in Saturday’s Financial Times (registration required) under the headline “A War To Die For But Not Control”:

Mr Obama’s multilateral approach to world order may look more legitimate in the eyes of the world, in the sense that it is more “legislated”. In the eyes of Americans, such an approach looks less legitimate. Relatively speaking, it separates control of international missions from the people, and from the class of people, who will die on them.

This drumbeat will continue in Sunday’s Washington Post – under the headline “As global crises mount, Obama has become the world’s master of ceremonies” – by David J. Rothkopf of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace:

Over the past two decades…presidents have carved out their own approaches. Buoyed by the Cold War victory and an economic boom, Bill Clinton eventually positioned himself as a sort of “President of the World,” using the nation’s uncontested superpower status to seek common ground and advance common goals. After Sept. 11, 2001, George W. Bush became “the decider,” the unilateralist, with-us-or-against-us president.

Now the world is witnessing an American president who appears less inclined or less able to assert his country — or himself — as the dominant player in global affairs. He seems more comfortable with the bully pulpit than the “big stick,” more at ease working within coalitions or even letting other nations take the lead where Washington once would have stood front and center.

So as war heats up in Libya in coming days – and as the U.S. plays a supporting role – the futures of both Gaddafi and Obama hang in the balance.