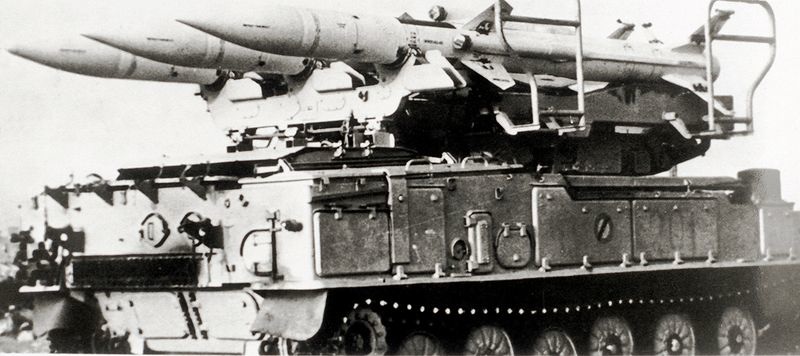

U.S. and allied warplanes would have to destroy Libyan SA-6 anti-aircraft missiles like these if a no-fly zone were ordered over Libya / Wikimedia

The debate over imposing a so-called “no-fly zone” over Libya to make sure Muammar Gaddafi’s air force can’t strafe his subjects from the skies is now in full swing. From the outside, it seems like a perfect answer: using a dram of airpower to protect helpless innocents on the ground. Of course, it’s never that simple.

The New York Times reports this morning:

…warplanes took to the sky for the first time in 10 days [Monday], according to military officials allied with the rebels. In a direct challenge to claims by those officials, who have asserted that Libyan Air Force pilots were no longer taking orders from Colonel Qaddafi, two Libyan Air Force jets conducted bombing raids on Monday, according to witnesses and two military officers in Benghazi allied with the antigovernment protesters.

Col. Hamed Bilkhair said that the jets, two MIG-23s that took off from an air base near Colonel Qaddafi’s hometown in the city of Surt, struck three targets, but were deterred by rebel antiaircraft fire from striking a fourth at an air base in Benghazi. The jets — a bomber and an escort plane — attacked three other locations, south of Benghazi, and on the outskirts of the eastern city of Ajdabiya.

Libyan rebels have made it clear they would welcome a no-fly zone over their heads, and even have selected targets to attack. But all that depends on how one defines a no-fly zone. In its purest sense, the only targets are aircraft in the air. Should a Libyan zone be expanded to include warplanes on the ground? What about the command post where air missions are planned, or the depots where the bombs, bullets and missiles the Libyan air force might use are stored?

Just as critically is how long would such an operation continue? If the imposition of a no-fly zone fails to topple Gaddafi, how long does the no-fly zone drag on? Or should air attacks and other offensive operations be stepped up, from the skies or elsewhere, to ensure the end of his rule in relatively short order?

Pentagon officials said Monday that various assets — most likely the carrier USS Enterprise and the amphibious ship USS Kearsarge — are being moved into position because of the Libyan crisis. Both warships carry aircraft that could be deployed to enforce a no-fly zone, although Pentagon officials believe international authorization would be needed first. Any U.S.-led operation could undercut, in some eyes, the legitimacy of the Libyan-led revolt, they said. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said U.S. officials are communicating with Libyan refugees and will aid those who have fled the country.

The Libyans have dozens of Russian SA-6 anti-aircraft missiles, which could down U.S. and allied warplanes. So the first mission in establishing a no-fly zone likely would require destroying the radars that guide those missiles.

No-fly zones have a checked history. The U.N. — but actually, largely the U.S. — maintained no-fly zones over northern and southern Iraq for about a decade following the first Gulf War in 1991. The northern third of Saddam Hussein’s country was deemed a no-fly zone and that was pretty successful, in part because of anti-Saddam Kurdish forces occupying most of that terrain. The southern zone didn’t work out so well, especially after Saddam was able brutally suppress a Shiite uprising immediately after the war, slaughtering tens of thousands with armed helicopters and other weapons, before the southern zone was put into place.

The Iraqis never succeeded in shooting down a U.S. or allied plane patrolling the no-fly zones — they flew more than 250,000 sorties — despite the promise of cash bounties for any Iraqi who downed a plane. But the U.S. Air Force did succeed — after misidentifying a pair of aircraft as Russian-built Iraqi Hind helicopters — in downing two U.S. Army UH-60 Black Hawks in 1994, killing all 26 aboard.