With the nation in two wars and faced with implacable Islamist foes, some argue that now is not the time to discuss cutting the defense budget. House Republican leaders barred spending cuts for the military, homeland security and veterans in their party’s “Pledge to America” campaign manifesto last fall. Last week, 165 members of the House’s 242-member Republican caucus unveiled their “spending reduction act” that places a Maginot Line around the roughly trillion dollars a year that the nation spends on the military and its various offshoots (VA, homeland security, &c.).

But there is a growing realization that to nurture and nourish a strong military — and GOP-leaning Tea Partiers may be in the vanguard here — that the Pentagon is going to have to be subject to the same kind of budget discipline that the rest of the government faces. It will involve short-term pain, but it’s the only way to ensure the long-term strength and vitality of the nation — which represents the foundation for a strong military. We’ll be dipping into this topic as the debate heats up, and examining smart ways to preserve security while spending less.

So let’s start by asking if our troops are paid too much.

The Pentagon’s single biggest cost is personnel, which — when everything is tallied up — accounts for close to 50 cents of every dollar spent. Few would deny soldiers risking their lives on our behalf a good paycheck, but the fog of war has clouded just how good those paychecks — and bennies not included in them, but still paid to the troops — really are. If we’re going to have a rational debate on defense spending, we can’t place troops’ paychecks off limits by claiming “there are soldiers on food stamps,” which is a regular cry of those who don’t want to scrub the Pentagon’s personnel accounts.

Congress recently ordered the Congressional Budget Office to place the cash compensation of soldiers on one side of the scale, and those earned by Uncle Sam’s civilian employees on the other side, and see how much each is making (remember — they’re both paid by taxpayers). They’re complicated calculations, and such complexities have been used by those who prefer the status quo to justify the status quo. But the status quo is no longer sustainable.

Here’s what the CBO finds in its just-released inquiry:

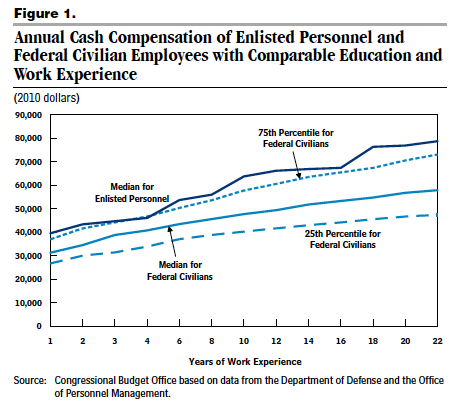

— Enlisted troops start at about $40,000 annually, when tax-free housing and food allowances are added into their base pay. Civilian government workers collect slightly more than $30,000.

— After 22 years on the job, the median enlisted compensation is about $75,000. The median civilian government compensation for workers with similar education is about $55,000.

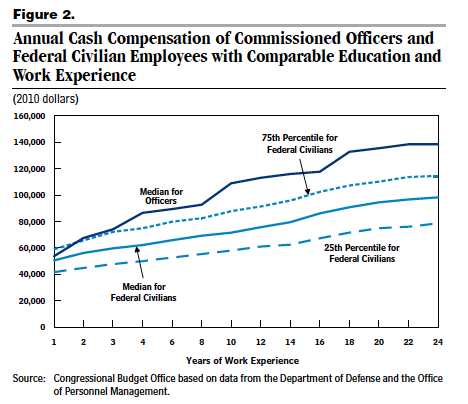

— Higher-educated officers, and the civilian workers like them, both earn about $50,000 in total compensation at the start of their careers.

— After 24 years on the job, officers wearing the nation’s uniform earn nearly $140,000 in total annual compensation, while their civilian counterparts earn about $100,000.

These figures don’t include non-cash benefits — subsidized health insurance and child care, for example — nor deferred benefits, such as pensions and VA care. Such benefits, the CBO estimated, add about 100 percent to a military person’s compensation, and 55 percent to a civilian’s. For those challenged by big numbers, that means a military officer with 24 years’ experience costs about $280,000 annually.