John Wheeler was one of those outer planets in the capital’s solar system, never drawing too close to the Sun but riding the country’s business in an elliptical orbit that would bring him closer to the heat every once in awhile. I can remember discussing the plight of Vietnam veterans with him — and their push for a memorial to commemorate their sacrifice — as well pondering the threat that cyber war posed to America. Sure, the topics were 180 degrees, and three decades, apart, but that’s the kind of Renaissance man Jack Wheeler was.

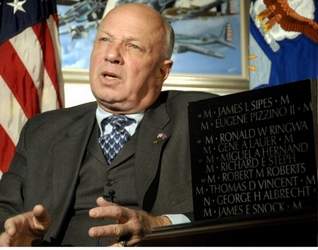

Jack Wheeler / Air Force photo

It came as a shock to all of us who knew him that Wheeler — West Point (1966), Harvard (1969) and Yale (1975) — ended up dead in a Delaware dump on Friday. There’s little publicly known about Wheeler’s final days, although he was believed to have been aboard an Amtrak train from the capital to Wilmington, Del., on Tuesday. His body surfaced as a trash truck — after picking up debris from 10 bins on the east side of Newark, Del., dumped its load at a landfill. Police have not specified how he died. He lived in nearby New Castle, Del., with his wife, Katherine Klyce, owner of a New York-based Cambodian silk company.

While he never saw combat in Vietnam, he felt that the war’s veterans had been ignored by their country, and joined forces with Jan Scruggs to build the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. Initially derided as a “black gash of shame,” it has become one of the nation’s most-visited and beloved monuments since its opening nearly 30 years ago. “I know how passionate he was about honoring all who serve their nation,” Scruggs said, “and especially those who made the ultimate sacrifice.”

Following his military service, Wheeler cycled between government jobs and the private sector, working for the Securities and Exchange Commission in the early 1980s, helping create the Vietnam Veterans Leadership Program in the Reagan Administration, and the Earth Conservation Corps during the first Bush Administration. He led Mothers Against Drunk Driving from 1985 to 1987, and ended his government career as a special assistant to the Air Force secretary from 2005 to 2008. “He was a complicated man of very intense (and sometimes changeable) friendships, passions, and causes,” long-time friend James Fallows said on the Atlantic website. “His most recent crusade was to bring ROTC back to elite campuses.”

He could be consumed by data: while an Army officer, he wrote the first Biological and Chemical Joint Munitions Effectiveness Manual, and the accompanying analysis supporting the government’s decision not to use biological weapons. He served on a team of experts that tested the nation’s nuclear war-fighting plans. Along those same lines — Wheeler fought all his life for the country to honor those who wore its uniform — he wrote last April about what he saw as a dearth of Medals of Honor being awarded to troops waging the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. It was vintage Wheeler, a stew of pride, patriotism and math:

I have done a notional analysis of the magnitude drop in the number of Medals of Honor in the OEF-OIF wars compared to earlier wars and the findings are telling. My calculations, which are preliminary but suggestive, are based historical data. The measure I use is 10,000 troop combat days (TCDs) for each medal of honor received –10, 000 TCDs per MOH…There is more than 20x throttling-back for OEF-OIF compared to prior wars. That is, more than a 95% cut in MOH awards compared apples-to-apples with other wars. Varying the assumptions does not change the order of magnitude of the comparative slowdown. This is a dramatic cutback in finding and honoring valor in OEF-OIF.

He suggested creating a Commission of Review for Valor Recognition to address this shortfall. Championing unheralded valor for unknown soldiers young enough to have been his grandchildren: that is Jack Wheeler’s legacy.